Tending to my relationship with science

Writing my dissertation required me to find a way to calmly and steadily extract my thoughts.

Impossible.

The once swirling series of my observations, academic literature and the visions: their dance of interdependence, had to be put into writing.

In order to wrangle it all, I became utterly dependent on painting to guide me through each decision :: from dreamland to reality.

Blue lotus flower:

The Flower of intuition

knows strategic transformation.

One morning the feminine opens

to receive

[pollen]

in its sunset pool.

Then, with the next rise,

its own golden granular expression:

[pollen]

the growth of the masculine.

Life light particles move in, yes.

and Great fully out-

Balance needs

whole opposites.

The paradox, embracing contradiction

in now.

It’s Love.

Its intuition.

For my final field season of my PhD in 2023, the only task I gave my self was to capture Draba plants in water color paintings for my presentations and my publications. Draba plants rarely photograph well. They are never quite as cute on camera as when I spotted them on my hikes. I wanted to be able to share their personalities more readily, so I set out to paint them in their habitats. I wanted to be able to show what each plant felt like and try to convey some of the messages their from body language was conveying to me, like how their leaf shapes changed depending on where they were growing and how their posture seemed to tell the story of their little plot of land. When I first sat down to start, I realized that I had no idea what to try to capture — which plants would be perfect to show the scientific story my genetic data would tell. Should I paint the flowering one? Should I capture the one that has some dying leaves and try to include the plants that are growing around it? What if I spent all this time and travel and had nothing of value to show? The voice of my nervous, eager to please, constantly moving first-year-student-self came back and wanted control. This time I recognized her anxiety. The rest of me knew to take special care of that part of me and slowly wrangled her to rest.

One of my most memorable field sites is Goshute Canyon in the Deep Creek Range in Western Utah. This mountain range is the only home to Draba kassii and requires me to drive across the Salt flats of Utah and through a ghost town and desert dirt roads. Finally to arrive at the entrance of the mountain range, where I ask my car to climb up the side of the canyon to the camp spot at the entrance. Once step out, I am locked in — I have no choice but to surrender what ever the unique mountain range and Draba species has to teach me that year.

In the summer of 2023 it was even hotter than usual with no relief at night to recover from the burning sunshine during the day. I hiked the north facing canyon walls to the rocks whose cracks were occupied by Draba kassii. Instead of trying to paint as many plants as I could the heat called me to lighten my task— to just paint one plant a day. With out the pressure to make too many beautiful things, I happily dwelled on the shape of the leaves to find how they really moved. I took breaks when I felt overwhelmed or bored— closed my eyes and quieted my mind and I landed my body along the crevice I was painting in. I came back to painting only when I found the energy again. From this cycle came an innovation. In sites before this one, I was painting Draba plants and made separate painting of their environments (some examples shown below in the slide from my research talk). Out of the rest and stillness, I started to paint the back grounds as impressions rather than grasping so desperately on to every detail of both Draba and the environment separately. Instead, the portraits depicted Draba as the main event as a part of the mountain scapes they lived in. Of course, the challenge to my energy levels presented by the Deep Creek mountains was what I required to simplify my strategy and create something new, something more true to me.

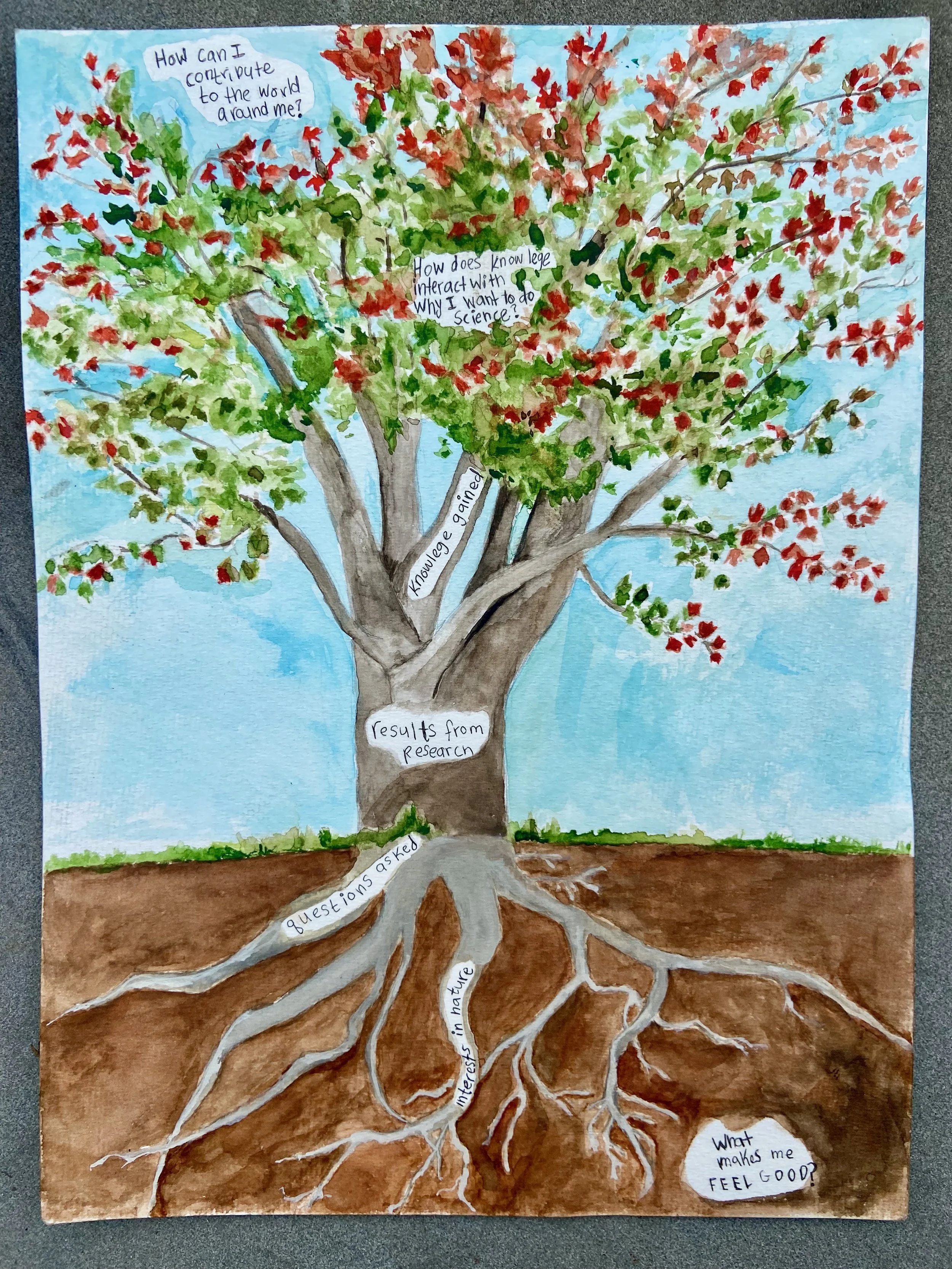

In July 2023, I attended the Botany conference in Boise, Idaho to run a workshop with the SciArt collective and present my dissertation research. The workshop shared and encouraged individual approaches to integrating art and science. We are determined to cultivate connection and diversity in the scientific community by celebrating distinct perspectives. The goal of the workshop was to appreciate that it is our unique individual creativity that opens new pathways resulting in resilience and innovation. Ultimately the workshop aims to diversify the scientific questions we ask and the solutions we investigate.

The slide above is from my research talk, where I shared my gene expression data, and growth and development phenotypes. These differ between populations of Draba albertina adapted to habitats with distinct climate variables. I included my water-color paintings of Draba (Brassicaceae), my study plants, and their environments. By including paintings of my study system, I not only presented information to support the scientific ideas, but I also prioritized communicating what the environment felt like. Along with my results, I integrated the story of my personal growth that was not only guided by but also enhanced the scientific process. My presentation showed that at the intersection of art and science is the human experience of nature. The process of building knowledge of the world around us is inseparable from the framework of perspective that is shaped by emotion and personal association. I shared how connecting to plants and my research with all parts of myself allowed me to bring an objective perspective to my science as well as my actions and how I connect to the world around me. Feedback from my audience made it clear that I created a much-needed space for my colleagues to connect more effectively to their work in academia that so often calls us to separate our minds from our hearts.

Draba rectifructa is the only annual species in the clade of North American Draba that my dissertation focusses on. I set out to look for it in Carson National forest in my first field season, but in my nervous haste, I missed them. I did not find D. rectifructa until my third field season in Gunnison National forest (painting on the left) to include their gene expression and grow out phenotypes in my research where I investigated the difference between annual and perennial Draba. It was not until my final field season that I found them in New Mexico. Before I began my drive east, I went to Carson again as a farewell retreat. My intention was to I take a few days of rest to be in the forest that was the most soothing to me. I chose this place to honor the mountains that I visited looking for Draba and the connection with my self, my passions and motivation the land taught me. Here, I said good bye to the mountains and pine trees that had supported me through the years of my dissertation driven field work, opening to my next steps and what I knew time of great change.

Just down the hill from my camp spot were several fields full of D. rectfructa all dried out in the late July sunshine. Grateful to have a project to put my love into during my days off, I painted them in their whimsical state (painting on the right). My perception of their whimsy was probably only a product of the fact that I painted them on days I had set a side as rest. And found them by accident. I had no time line and no obligation — other than to capture this species as they stood with ease in New Mexico.

At the international botanical congress in Madrid (July , 2024), I shared the ways I practiced art and science as I developed three data chapters. When I started my PhD program, I struggled with the sterile environment of academic science. It seemed to be a world without emotion. When I tried to adopt scientific culture I froze, I could not find energy to move forward so I had to choose between leaving science or finding a way to integrate my emotions into the practice of science. I decided to let what I learned about Draba teach me about my own personal patterns, to identify the patterns of behavior and thought that no longer served me and to find a way to untangle the knots that blocked me from being present with myself, my interaction with community and nature.

I entered science because when I encounter nature, I want to understand the way biology works and figure out how a plant got to be so complex and intricate. When I got to there, the culture that valued and enforced uniformity in the scientific process stifled the curiosity that drove me to science. Publishing fake data just for the sake of money and reputation and student’s use of AI generated responses to in their homework, rather than investigating in their own thought processes, are examples of how society has gotten lost the priority of output and have become disconnected from the process of work. Personal exploration has been cheapened by the industrious mindset and lead to the depression and anxiety so many of us experience. Throughout my time in science, I have encountered a large community of people who feel drained by the pressure to conform rather than replenished by the ability to follow curiosity and connection to the natural world in their work.

In response to the ways science and society have both become disconnected from the true gifts of the creative process and the natural world, I have developed the intersection of art and science as a place for self-discovery and to build intimate connections to the world around us. When I spoke at the international botanical congress in Madrid ( July , 2024), I integrated my personal growth into the story of my data for all three chapters of my dissertation work and was received by tears of gratitude. I was thanked for my vulnerability and honoring for the profound connection each of has to the earth. In the unification of art and science, my goals are to guide others in discovering their emotions and deepest motivations through learning about ecology and evolution. Using nature as a mirror and a source of energy that comes from new understanding, we can find our way back to ourselves and greater purpose. Moving forward, I devote myself not only to continue to uncover the mysteries of Draba but also to carve out space in the scientific setting for the human experience in the interaction of my art and research practice. Our future calls us honor the diverse and complex emotion that underpins all things we do and become connected to an even deeper sense of objectivity that comes with self-awareness. By integrating the human experience, we will contribute science that reconnects humanity to itself and to its truth as a part of nature.